How do You Use Float to Make Money?

“Float” is a financial concept that has been used in both personal and business accounting for a long, long time. In simple terms float is the temporary double use of an asset or valuation, including money.

The most common example used to explain float involves writing a check. On Friday you write a check for $100 to Sam. The $100 is in your account. On Saturday Sam deposits the check in his account. Even by today’s lightning-swift banking processes, Sam’s bank probably won’t receive the money for the check from your bank until Monday or Tuesday. So from Saturday until whenever your account is debited for $100 that money “exists” in both places.

If both you and Sam are using interest-paying checking, you can both earn interest on the $100. For Sam the $100 is simply money in the bank that will stay there until he spends it. But for you that $100 becomes “float” from the moment you write the check (obligating your bank to pay Sam or his bank $100) until your bank pays the check from your account.

Float Acts Like a Temporary Loan

In any transaction, if are able to make use of money between the time you obligate yourself to pay it to someone else and they collect, you are working with float, and that works something like an interest-free loan. Of course, most people will never be able to use their float to make money, except maybe to earn a little bit of interest while the money is in transition between payor and payee.

But assuming you can work with a longer period of float while still meeting your financial obligation you may be able to use that money to make more money. Take the practice of post-dating checks. People do this when they don’t have the money today to honor a check but someone agrees to hold that check until a certain date, at which time the payor promises the money to cover the check will be on deposit at the bank.

What if you could get someone to give you value today for a post-dated check even though you had the money to cover the check? That would create float you could then use to buy and sell something else, possibly making a profit.

Oddly enough, large retailers sometimes offer exactly these kinds of deals. For example, you may be able to buy $10,000′ worth of furniture at 0-percent interest if you agree to pay off the loan in 12 months. Or you may get a 0-percent interest loan for a car. Keeping in mind that these sellers are still making money somehow, you’ll still have float to work with if and only if you could pay for the merchandise in full at the time of sale.

So if you don’t have $10,000 for new furniture today then taking a 12-month, 0-interest loan on that furniture does not create $10,000′ worth of float. It only creates as much float as you would have money in your account at the time of purchase that you were prepared to part with for the furniture. That might be $10, $100, or maybe even $1000. So just getting a 0-interest loan does not mean you have created float.

Float is Created by Rapid Selling and Slow Buying

Suppose you are buying and selling stocks. You can buy the stocks in advance or you can sell them in advance. You can also buy and sell stocks at the same time. Most people buy stocks first and then sell them later, but some people sell stocks first and then pay for them later.

You’ll see advanced stock selling in the so-called short market where — as a stock price declines — a short seller borrows shares from a broker at today’s prices and pays the broker back at a later date for a lower price. The broker may be willing to lend the shares to the short seller in the hope of earning transaction fees, or thinking that the stock price will go back up before the short seller has to pay for the shares.

Meanwhile, regardless of what happens to the stock price, until the seller has to settle his obligations he is free to do whatever he wants with the money he made by selling the stock. This is called float provided he meets his obligation to buy the shares from the broker at the agreed time and price. It’s called a disaster if the short seller cannot meet his margin call.

In other words, you create float by collecting money that is not all entirely yours to own by deferring your transfer of that money to whomever you owe it to. The deferment of the transfer of wealth is the float.

A Consignment Sale is a Form of Float

If you move out of state and decide not to take your furniture with you, you may put it up for sale in a consignment store. The store pays you only if they sell the furniture. The furniture store enjoys the benefit of a floating asset (your furniture for sale in their showroom) without actually having to pay for it in advance.

You might become a consignment seller yourself. For example, suppose you have a friend who has a stereo system he is no longer interested in owning. You know that this is a vintage entertainment system that may attract some good buyers on eBay or Etsy. You happen to have an account on one or both of those services, so you offer to find a buyer for your friend, taking a small cut of the sale price.

You have created an asset float as long as you and your friend keep your bargain. If, however, when you make a sale your friend backs out of the deal you are still obligated to the buyer to do something. You may refund the buyer his money, try to find a similar item at a reasonable price, or you may try to negotiate substituting another item (I include this only for illustrative purposes — buyers probably won’t write good reviews if they think you are baiting-and-switching).

The float exists only from the time the obligation is created until it matures (comes due), but you can float physical assets as well as intangible assets.

Warren Buffet Uses Float All the Time

Warren Buffet, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, is widely regarded as the most shrewd businessman and investor in history. His company owns insurance companies (the most famous of which is GEICO, the company with the Gecko and Cave Men mascots). Insurance companies collect premiums from customers and pay those premiums back to settle claims against customer’s insured losses.

Every time an insured house burns down thousands of premiums from other homeowners are used to reimburse the family whose house was destroyed by the fire. This form of shared loss recovery was developed thousands of years ago by small communities of farmers and merchants who helped each other out in times of disaster. In fact, every time the government steps in with financial assistance to help victims of natural disasters like earthquakes and great storms they are redistributing tax-payer money to tax-payers just like an insurance company does.

Berkshire Hathaway takes the premiums its customers pay in and invests that money in stocks, bonds, and other assets in the hope of earning extra money before they have to pay out claims. Of course the process of collecting premiums and paying claims goes on continually but in an accounting process you can keep the money working for you “on the books” for a while.

This float ensures that Berkshire Hathaway (and other large insurers) has sufficient financial reserves to handle unexpected disastrous losses. For example, every time a huge hurricane devastates many cities the insurance industry takes a huge loss — and that is because they collect less money through premiums in that year than they pay out in claims.

So don’t resent the fact that insurance companies use your premiums as free loans for investment. Even though Warren Buffet is very wealthy, the fact his insurance companies are sell well-funded protects their clients against large-scale disasters.

Other Forms of Float You May See in Business

Have you ever bought a product and mailed in a request for a rebate check? The company making the sale to you has already treated that rebate as a financial obligation it owes to you. If you don’t collect the rebate then they can pocket the money and do whatever they please with it.

Have you ever bought a product and mailed in a request for a rebate check? The company making the sale to you has already treated that rebate as a financial obligation it owes to you. If you don’t collect the rebate then they can pocket the money and do whatever they please with it.

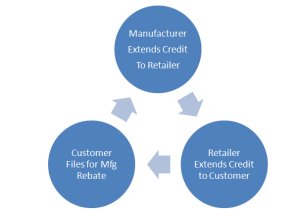

But between the time you buy a product and their bank pays off a rebate check they are benefiting from a free loan. The way big business works now, that loan may have begun before you bought the product — assuming you purchased it from a retailer who paid for the product in advance. But what most people don’t know is that many retailers “buy” products on credit from manufacturers. This credit-based transaction means the retailers don’t have to pay for the merchandise before they sell it. Hence, there may be two floats in action behind the sale of a microwave oven.

What’s even more cool is that you may be able to buy merchandise that comes with a rebate through an in-store credit program where you pay no interest if you pay the full sale price within 30 days. So even though you have the $100 for that microwave in your bank account today you float it by purchasing the item on your retailer credit card; the retailer bought the microwave on credit from the manufacturer and only pays them after they collect the money from your sale; and the manufacturer is waiting for you to mail in a rebate claim (which they may take 6-8 weeks to settle).

Everyone comes out ahead by NOT spending any money right away. The bottom line here is that if it’s makes sense to borrow money (doing so costs you nothing) AND you can use that money for something else even for a little while, then you’re taking advantage of a float that is perfectly legal. Just remember that the transaction creates a real obligation that must be honored.

Cornering the Market in a Given Float

In very rare situations you may have the opportunity to buy all the stock in an item with a rebate at a discounted price. Retailers may offer these kinds of deals if they cannot move merchandise fast enough. Or they may be selling the items as loss leaders, hoping to bring in customers who will buy other, more profitable merchandise.

20-30 years ago you might find a guy at a local flea market selling brand new merchandise he bought at a discount. If he was both lucky and shrewd he may have found merchandise offering rebates and sent in the proof of purchase for the rebate claims. Imagine getting back $10 each for $100 hunting knives that you bought at a $25 discount and then selling those knives for a $15 discount (off suggested retail price) at the flea market. You make $10 on the sale of each item and get another $10 in rebate for each item.

In the worst-case scenario you’re stuck with 100 hunting knives no one wants to buy but they only cost you $6500 (plus tax). Sooner or later you’ll find buyers for those knives so you may get your money back eventually. Still, you only need to sell 77 of those knives to get your money back.

So who gets the float in this kind of transaction? Well, the manufacturer does because they will hang on to the rebate money for as long as possible.

But the guy at the flea market is benefiting from that rebate as well. He treats the rebate as a discount on his cost of acquiring the merchandise he sells. It’s a temporary expense to him rather than a permanent cost-of-goods expense.

Anyone who buys the knives at the flea market still gets a 15-percent discount off suggested retail price, which is a good deal if they really want that particular hunting knife and cannot find it in local stores (or cannot find as good as price as the flea market guy offers). Maybe only the initial retailer loses in this transaction, but even they may have unloaded the knives at a slight profit.